It feels like you’re on top of the world. Ahead is Mount Rainier, with its rounded peak wreathed in snow. All around are clouds so thick and substantial you think you could walk on them to the other peaks, like majestic Mount Adams, that poke through.

This is Susan Kaspari’s world. Over the years, the CWU geological sciences professor has spent many days and nights studying places like Mount Rainier to determine how natural and manmade factors impact snow and how it melts.

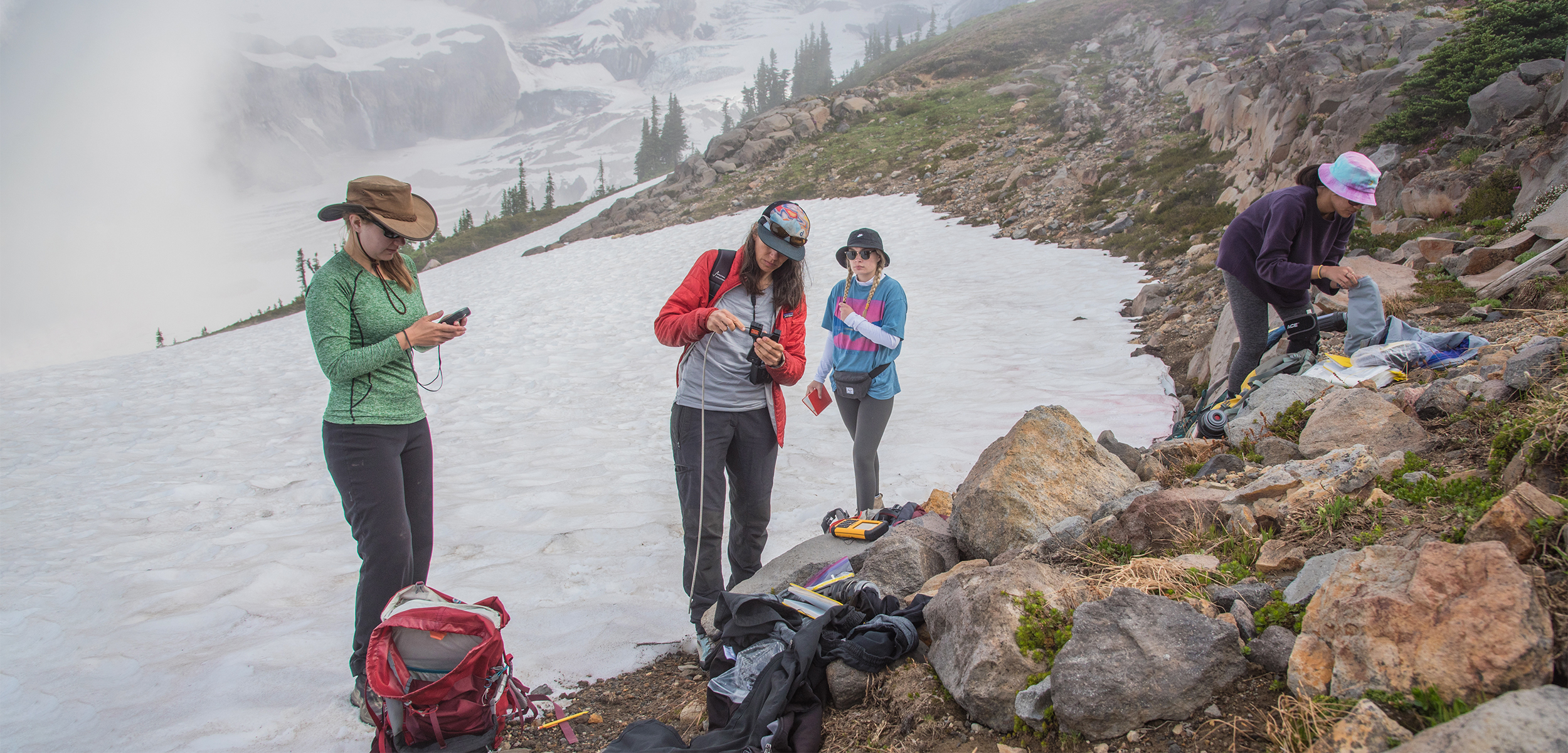

Last summer, Kaspari and three CWU undergraduate students—Stephanie Bartlett, Erliana Acob, and Rylynn Carney—made the trek to the slopes of Mount Rainier, which is the highest mountain in the state of Washington, to collect snow samples and measure the reflectiveness of the snowpack.

“This really is our decade to do something about the climate, and we have got to buckle down and do things now.”

—Susan Kaspari

“The aim was to provide the students with undergraduate research experiences, especially with instrumentation,” Kaspari said. “They collected samples that they then spent the rest of the summer measuring in the laboratory.”

She said all three students, who she had taught in classes last year, had approached her individually to ask about field research opportunities.

“They were all really good in the field,” Kaspari said. “And they worked together so well in the lab this summer. They were just such a pleasant group to work with and it was a really great experience.”

One of the students, Bartlett, said the field work was enjoyable but worrying at the same time.

“We had a great team, and we were surrounded by breathtaking views. However, when our attention was diverted from the scenery to the snow, I was shocked at how much snow algae we saw,” she said. “I never realized how dirty the snow on mountains was before, and I was also intrigued by the varying types and colors of particles on the snow over a small area.”

Bartlett said the experience opened her eyes to the impact humans are having on the climate and environment of the planet.

“It has inspired me to put a lot more effort into mitigating my own personal impact on our environment,” she added.

Kaspari said the Mount Rainier research was part of larger body of work focusing on light-absorbing particles on snow that she has been doing since arriving at Central in 2009. That work has taken her, often with students, to Mount Olympus, Lake Ingalls in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, South Cascade Glacier, and other places throughout the Cascades.

“For a long time, I have worked to collect ice cores from around the world and we use them to reconstruct climate and environmental conditions,” she explained. “The second focus of my research is looking at light-absorbing particles. These include black carbon, dust, organic material, and volcanic material.

“As you know, snow, when it’s fallen freshly from the sky is very white and reflective. When light absorbing particles are deposited on the snow surface, the snow surface is darkened, and then the snow absorbs more energy from the sun, and that causes accelerated melt,” she continued.

The result of the more rapid snow melt is a loss of snowpack, which serves as a natural water reservoir for the Pacific Northwest region during the warmer months, as well as increased flooding.

Kaspari said while some particulate matter in snow is natural, such as dust from eroded and crumbling rock, some can be traced to things such as the burning of fossil and bio fuels, smoke and ash from wildfires—particularly bad this year—as well as dust created by agriculture and other land use change.

Kaspari explained that snow is typically whiter in the winter, when it is freshly fallen, then turns dirtier through the dry summer months. She noted that at higher elevations on Mount Rainier, where multiple years of snow accumulation is preserved, she can see alternating layers of white and darker bands, which show the seasons.

Kaspari and her students also studied snow algae at Mount Rainier. According to Kaspari, snow algae manifests in pink-colored patches (also known as watermelon snow). In some regions of the world snow algae is increasing due to more liquid water in the snowpack and changing nutrient availability supporting more algae growth.

She said the biggest reason for the changes she is seeing is climate change, which plays a major role in creating the conditions that are impacting the snow.

“First of all, we absolutely see less winter precipitation falling as snow. More precipitation is falling as rain, and that water is going into the rivers in wintertime instead of being stored in the snowpack,” Kaspari said. “We’re seeing less accumulation in the snowpack and the snow is melting earlier in the spring. All of these changes are driven by climate change.”

Kaspari was honored as CWU’s 2021 Distinguished Professor for Service for her role in supporting efforts to promote sustainability at Central over the past decade. She said efforts such as the Paris Agreement, which commits countries to reduce their carbon emissions and take other steps to combat climate change (the United States recently rejoined the accord), are a big step in the right direction.

“Paris is phenomenally important,” she said. “What you hear in the news about the impacts of climate change are true, and now is the time for action. This really is our decade to do something about the climate, and we have got to buckle down and do things now.

“In the U.S., we need to fight for more substantial climate legislation that’s going to support transitioning away from fossil fuels and to a cleaner energy economy,” she added. “And that needs to happen now.”

comments powered by Disqus