As the oldest of five, Veronica Guadarrama knew her parents expected her to lead the way after graduating from high school.

Her parents wanted their children to achieve what they hadn’t: a college education.

“My dad understood it was key to better jobs, to more stability. There’s a lot that you can learn when you go to college,” she said. “He’d always tell us, ‘Knowledge is one of those things that can never be taken away from you.’”

Guadarrama graduated from CWU in 2015 with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics (secondary teaching) and a minor in sociology. Today, she’s helping other first-generation students in Washington find their path toward success as the director of TRIO Student Support Services at Big Bend Community College in Moses Lake. She’s also president of the Washington State TRIO Association.

It’s a story that repeats itself time and again among those who serve first-generation students.

Central’s director of Latino and Latin American Studies, Dr. Christina Torres García, is a prime example. She is the daughter of Mexican migrant workers and immigrated to the U.S. as a child. Growing up in the 1990s, she had to advocate for her own education and convince teachers that her lack of English-language skills was not a disability.

She recognized that she had to take charge of her own higher education journey, and today she is mentoring a new generation of young people.

“I’m definitely a walking testimonial for the work that the TRIO programs do,” said Torres García, who like Guadarrama was a McNair Scholar.

These educators and others like them have a passion for helping first-generation students and helping them connect with the networks they need to be successful.

••••••

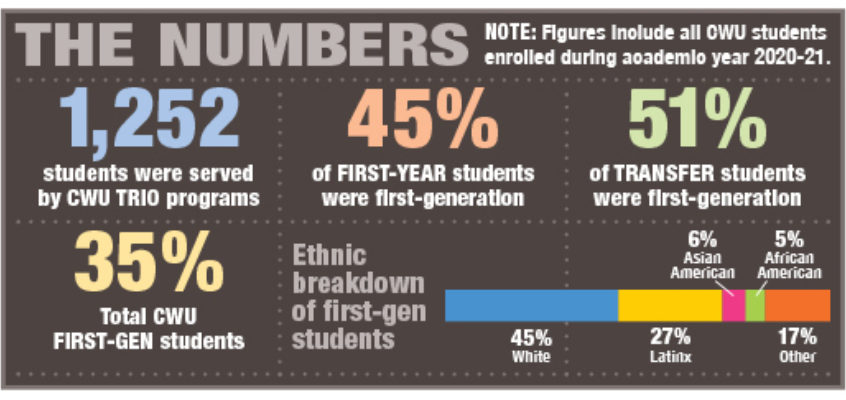

Numbers at CWU

In 2020, TRIO programs in Washington served just over 16,000 participants, the majority of whom come from families whose parents don’t have four-year degrees. According to the most recent data, CWU’s programs worked with 1,252 students in 2020. Those numbers have been relatively steady in recent years and are just one way that educators across the state can track trends with the first-gen population.

In the fall of 2021, for example, approximately 45% of first-year students at Central were first-generation—one of the highest among the state’s public four-year institutions. For the same period, Washington State University reported 34.3% of its undergrads were first-generation; University of Washington, 30%; Western Washington University, 27.1%; and Eastern Washington University slightly higher at 36%.

Central’s numbers are even higher for transfer students—a full 51% of them were first-generation, according to the 10-day census numbers in 2021.

While still high, first-generation enrollment is trending downward statewide, according to Joel Klucking, the chief financial officer at CWU who also oversees enrollment management. In 2015, the number of first-generation students at Central was closer to 50%, he said. Heading into the 2022-23 academic year, he anticipated that number to be around 43%, adding that other colleges in the state are seeing similar trends. Some of the drop-off can be attributed to fallout from the pandemic.

“There’s a strong job market right now, so people who are on the bubble about going to college or working have more opportunities,” Klucking said.

The other factor is the population of first-generation students is shrinking. “If half of our population has been first-generation students, eventually, you’re going to run out of people who are first-gen,” Klucking said. “If they stay in Washington and have kids, those kids aren’t going to be first-generation. So, there’s less potential for first-generation students for all the state schools to draw from.”

While Washington state residents rank near the top for overall education level, the number of in-state students who go on to college after graduation is among the lowest in the nation. In 2018, only 53% enrolled in some form of continuing education after high school, according to the National Center for Higher Education Management. That’s lower than the national average, and the fifth worst in the country.

“We historically have not had a super strong college-going population in this state,” Klucking said.

Breaking the Cycle

Convincing students that college offers a better path forward is difficult in normal times, but the pandemic economy has made it even more of a challenge. The enrollment team at Central works to bring students to campus so they can meet staff, faculty, and other students. Those programs also allow them to picture themselves in that environment.

“They have to compare the feeling they get from visiting Central and the potential they see to improve their future, with the idea that they could stay home and get $18 an hour working at McDonald’s,” Klucking said. “That’s hard to do when you’re 18.”

Parental support—like what Guadarrama had—can make a huge difference, but TRIO programs also play an instrumental role. The collection of federally funded outreach programs is designed to serve students from underrepresented backgrounds, such as low-income, first-generation students and those with

disabilities.

TRIO has several branches: Upward Bound and Talent Search for pre-college students; Student Support Services for undergraduates; Educational Opportunity Centers (EOCs) to work with adult students; and the Ronald E. McNair Postbaccalaureate Achievement Program, aka McNair Scholars, which focuses on placing students in graduate school. Those programs, and others like them, can help young people find their community and feel like they belong on campus.

“When students are looking at transferring from Big Bend, they get nervous. They wonder ‘How do I find my place? How do I find my niche on such a big campus?’” Guadarrama said, adding that she tells students that she’s from a similar background and shares the things she wishes she’d known as an undergraduate.

Meeting Their Needs

A university’s work doesn’t stop once the student is enrolled; they have to stay enrolled and graduate. “The worst-case scenario is you come to college for a quarter or two or three, and you drop out,” Klucking said. “You aren’t going to get a better job because of it. You have debt. You have negative feelings about your ability to be successful. That’s a terrible situation to be in.”

The support offered by peer groups, faculty, and programs like TRIO—including assistance with applications for scholarships and financial aid—can make a huge difference.

“The best way to lose a first-generation student is to speak to them like a second- or third-generation student,” Klucking said. “They don’t understand the acronyms. They don’t feel like they belong. I’m a third-generation college student; my dad was a professor. I knew what a registrar was, what it meant to live in a residence hall. But if you’ve never been on a campus before, that’s all pretty scary.”

Central focuses on early outreach, like the financial aid programs offered by the EOCs and partnerships with community colleges, such as Big Bend. They look for opportunities to bring high school and junior high students to campus so they can become familiar with the environment.

“We want them to feel like they belong on a college campus,” Klucking said. “Sometimes they can sit in on a class and realize that a college English class is really no different than their own English class. They start imagining themselves in college.”

Guadarrama sees three big issues for first-generation students: finding community, paying for college, and getting through classes to finish a degree.

Torres García acts as a mentor, and she understands that for first-generation students, that sometimes means checking on their physical and emotional needs along with their academic needs. What is home like for them? Are they taking care of siblings and parents?

“As I am mentoring my students, I’m also having conversations with family members to assist them with the transition to college,” she said. “If a particular female first-gen student tells me, ‘Hey, my mom is having concerns about XYZ,’ then I will ensure that when I see her mom that I bring it up and see what those concerns are. It is about helping these communities understand how to navigate college. Teaching not only the student but also family members.”

••••••

Future Predictions

In the coming years, Klucking thinks colleges will continue to see slowly decreasing numbers of first-generation students. Economic recessions and times of growth also typically shift the types of students who are attracted to college versus the workplace.

“I think we’ll see a little rebound in the near-term, depending on what happens with the economy,” he said. “These are the students who have choices; they aren’t convinced that college is the right way to go. If the job market isn’t as strong, historically people tend to go to college.”

And as schools become better at identifying the needs of first-generation students, Torres García hopes the struggles they face will lessen. But it will take work.

“We know that when higher education was implemented, it was not implemented to be inclusive of this kind of diversity,” she said. “Higher ed was created for middle- and upper-class white male individuals. When it comes to modifying or reforming systems that have been in place for centuries, there’s a lot of work still to be done.”

But changes are underway at CWU and elsewhere, such as the launch of a new financial literacy program next year. The pandemic shined a light on the inequalities for students, from access to wireless internet to home study spaces to the needs of their families.

“I believe COVID-19 shook the foundation of higher education and made us all realize that it must change,” Torres García said. “If we want to survive, higher education has to be modified to be inclusive and equitable for all students.”

comments powered by Disqus